Working Notes, November 2024

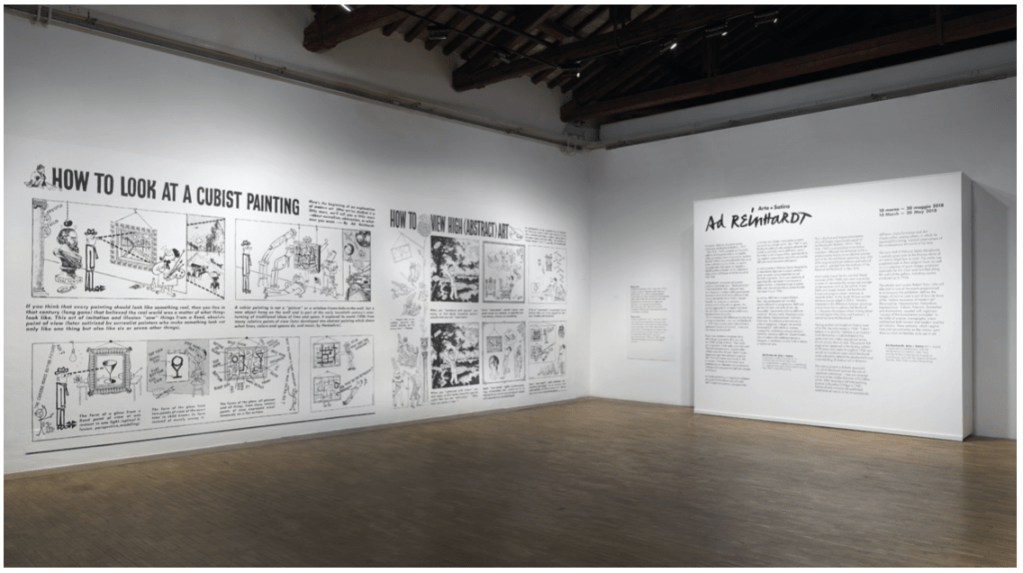

“How to Look at a Cubist Painting”

P.M., January 27, 1946

Among the recurring characters in Reinhardt’s sharp-witted cartoons is a Cubist painting that talks back to an uncomprehending viewer. “Ha ha, what does this represent?” asks the viewer, pointing at the painting. To which the painting replies angrily, “What do you represent?” Reinhardt embraced the aesthetics of Cubism and European Constructivism. In this collage, he carries forward the pioneering collage work of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque with an energetic composition of cut and pasted printed paper on board. Reinhardt updates the contained quality of Cubist composition by employing the allover aesthetics of the New York School, expanding his collage out across the surface of the board to its very edges.

– Museum of Modern Art, New York [accessed 21.10.2024]

“A painting is not a simple something or a pretty picture or an arrangement, but a complicated language that you have to learn to read.”

“After you’ve learned how to look at things, and how to think about them, clear up the problem of what you personally represent.”

Key words and phrases:

’Cubist Painting’

’REPRESENT?’

’how to look at things’

‘how to think about them’

Ad Reinhardt

1. ‘Cubist Painting’

In the art of the twentieth century, Cubism occupies a position as important as that of Romanticism in the nineteenth. The Cubist movement, gradually forming in the second half of the first decade of the twentieth century and developing up to the end of the second decade, marks a major turning point in the history of art.

– Christopher Gray: ‘Cubist Aesthetic Theories’, The John Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1953, p3

Picasso’s and Braque’s way of organizing a picture was borrowed, adapted, or fought against by almost all subsequent art, and very often taken as the still point of modernism — the set of works in which modernity found itself a a style. [p175]

[. . .]

This look is not misleading. There is a quality of insistence and repetitiveness to Cubism that sets it apart from all other modernisms, even the most dogged — even Mondrian. Monochrome, again, is one sign of that “back to the drawing board” frame of mind. [p191]

[. . .]

Evenness and openness did seem to mean better painting — had not that been Braque’s essential proposal to Picasso for the preceding three years? — but they also meant empyting, reducing, diagrammatizing, blanking out. [p192]

[. . .]

“We are arriving, I am convinced, at a conception of art as vast as the greatest epochs of the past: there is the same tendency toward large scale, the same effort shared among a collectivity. If one can doubt the whole idea of creation taking place in isolation, then the clinching proof is when collective activity leads to very distinct means of personal expression”: thus Léger in Montjoie! in 1913.” [p222]

– T. J. Clark: ‘Cubism and Collectivity’, in ‘Farewell to an Idea, Episodes from a History of Modernism’, Yale University Press, 1999, pp169-223

The great revolution…was to make the world in his representation [idea?] of it . . . A new man, the world is his new representation [idea?].

– Apollinaire: ‘Peintres cubistes’, Méditations Esthétiques, 1913

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was an art dealer turned publisher and writer, who became the pioneering champion of Cubism as the first dealer to sign exclusive contracts with Cubist artists such as Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso and as an early theorist of their work. He opened his first gallery, Galerie Kahnweiler, in Paris at 28 rue Vignon in May 1907.

– The Met / Modern Art Index Project [accessed 21.11.2024]

Kahnweiler, strongly impregnated with The World as Will and Representation, places Schopenhauer on the highest level; he retains his transcendental idealism and not the pessimism, and is willing to admit that he always interprets Kant through him.

– Pierre Assouline: ‘An Artful Life: a Biography of D.H. Kahnweiler, 1884-1979’, Fromm International Publishing Corp, 1991, p244

2. ‘REPRESENT?’

Painting is a mode of representation.

– Georges Braque, in Maurice Raynal: ‘Modern French Painters’, December 1917

The world is my representation”: this is a truth valid with reference to every living and knowing being, although man alone can bring it into reflective, abstract consciousness.

– ‘The World as Will and Presentation by Arthur Schopenhauer, Volume 1’ (1818), trans. E.F.J. Payne, Dover Publications, inc, New York, 1969

Vorstellung is important, for it occurs in the German title of this work. Its primary meaning is that of “placing before,” and it is used by Schopenhauer to express what he himself describes as an “exceedingly complicated physiological process in the brain of an animal, the result of which is the consciousness of a picture there.” In the present translation “representation” has been selected as the best English word to convey the German meaning, a selection that is confirmed by the French and Italian versions of Die Welt als Wille and Vorstellung. The word “idea” which is used by Haldane and Kemp in their English translation of this work clearly fails to bring out the meaning of Vorstellung in the sense used by Schopenhauer. Even Schopenhauer himself has translated Vorstellung as “idea” in his criticism of Kant’s philosophy at the end of the first volume, although he states in his essay, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, that “idea” should be used only in its original Platonic sense. Moreover, confusion results in the translation of Haldane and Kemp from printer’s errors in the use of “Idea” with a capital letter to render the German Idee in the Platonic sense and of “idea” for the translation of Vorstellung as used by Schopenhauer. In the present translation Idee has been rendered by the word “Idea” with a capital letter.

– Translator’s Introduction, ‘The World as Will and Presentation by Arthur Schopenhauer, Volume 1’ (1818), trans. E.F.J. Payne, Dover Publications, inc, New York, 1969

3. ‘how to look at things’

The subject is not the object of painting, but a new unity, the lyricism that results from the mastery of a method.

– Georges Braque, in Maurice Raynal: ‘Modern French Painters’, December 1917

For, “no object without a subject,” is the principle which renders all materialism for ever impossible. Suns and planets without an eye that sees them, and an understanding that knows them, may indeed be spoken of in words, but for the idea, these words are absolutely meaningless. [. . .] …the original mass had to pass through a long series of changes before the first eye could be opened. And yet, the existence of this whole world remains ever dependent upon the first eye that opened, even if it were that of an insect. For such an eye is a necessary condition of the possibility of knowledge, and the whole world exists only in and for knowledge, and without it is not even thinkable. The world is entirely idea, and as such demands the knowing subject as the supporter of its existence. This long course of time itself, filled with innumerable changes, through which matter rose from form to form till at last the first percipient creature appeared,—this whole time itself is only thinkable in the identity of a consciousness whose succession of ideas, whose form of knowing it is, and apart from which, it loses all meaning and is nothing at all. Thus we see, on the one hand, the existence of the whole world necessarily dependent upon the first conscious being, however undeveloped it may be; on the other hand, this conscious being just as necessarily entirely dependent upon a long chain of causes and effects which have preceded it, and in which it itself appears as a small link. [p38]

But the world as idea, with which alone we are here concerned, only appears with the opening of the first eye. Without this medium of knowledge it cannot be, and therefore it was not before it. But without that eye, that is to say, outside of knowledge, there was also no before, no time. Thus time has no beginning, but all beginning is in time. Since, however, it is the most universal form of the knowable, in which all phenomena are united together through causality, time, with its infinity of past and future, is present in the beginning of knowledge. The phenomenon which fills the first present must at once be known as causally bound up with and dependent upon a sequence of phenomena which stretches infinitely into the past, and this past itself is just as truly conditioned by this first present, as conversely the present is by the past. Accordingly the past out of which the first present arises, is, like it, dependent upon the knowing subject, without which it is nothing. [p39]

– ‘The World as Will and Presentation by Arthur Schopenhauer, Volume 1’ (1818), trans. E.F.J. Payne, Dover Publications, inc, New York, 1969, pp38 & 39

4. ‘how to think about them’

I confess, by the way, that I do not believe that my theory could have come about before the Upanishads, Plato, and Kant could cast their rays simultaneously into the mind of one man.

– Arthur Schopenhauer: ‘Manuscript Remains: Early Manuscripts (1804–1818), vol. 1, trans. E.F.J. Payne, Oxford: Berg, 1988, p467

After all these years I think now that for a long time I’ve paraphrased Schopenhauer, saying, “Interest is of no interest in art.”

– Ad Reinhardt: ‘Monologue’ (Mary Fuller, taped 27 April 1966), excerpted Artforum 9, no. 2 (October 1970) and reprinted in Barbara Rose (ed): ’Art-as-Art’, University of California Press, 1991, p24

5. Ad Reinhardt

Endless repetition of infinite sameness

Presence and absence of all meaning

End of history, anti-history

Subversion of own meanings

Devalue art, “the painting does not matter,” art-kind of enemy

Expose exorbitance of claims made for art

“Fabulous, formless darkness”

Museum, “place of the muses”

“Upshot of Upanishads,” one god, gone is one, one is god

Gap, gap between art & life “pop-abstraction”

“What manner of painting shall we paint?”

Artist, maker of anti-environment, enemy of society, criminal, saint

Circle-men, lozenge-men, rectangle-men

Shore-men (fish), plains-men (grain)

Puritanic, rabbinic, hasidic, Islamic, Buddhist, tantric

Image of images, symbol of symbols, sign of signs /

Painting, art of arts

“The temple is holy because it is not for sale” tart remark

– Ad Reinhardt: [ART–AS–ART], Unpublished notes, 1966-1967, Barbara Rose (ed): ’Art-as-Art’, University of California Press, 1991, p77 extract

–> artist–as–artist | conscience, consciousness

pure artist

abstract artist

– Ad Reinhardt: Unpublished, undated notes, Barbara Rose (ed): ’Art-as-Art’, University of California Press, 1991, p139

[further notes]

HA HA WHAT DOES THIS REPRESENT? WHAT DO YOU REPRESENT?

Arthur Schopenhauer: ‘The World as Will and Presentation’, 1818

[Book III] the object of aesthetic contemplation and, for a brief moment, escape the cycle of unfulfilled desire as a “pure, will-less subject of knowledge” (reinen, willenlosen Subjekts der Erkenntniß) / a will-less perception / “concerned with that which is outside and independent of all relations, that which alone is really essential to the world, the true content of its phenomena, that which is subject to no change, and therefore is known with equal truth for all time, in a word, the ideas, which are the direct and adequate objectivity of the thing in itself, the will…” / sinking into perception, “losing [himself] in the object, forgetting all individuality, surrendering that kind of knowledge which follows the principle of sufficient reason, and comprehends only relations…” / “We must therefore assume that there exists in all men this power of knowing the ideas in things, and consequently of transcending their personality for the moment, unless indeed there are some men who are capable of no aesthetic pleasure at all. The man of genius excels ordinary men only by possessing this kind of knowledge in a far higher degree and more continuously. Thus, while under its influence he retains the presence of mind which is necessary to enable him to repeat in a voluntary and intentional work what he has learned in this manner; and this repetition is the work of art.” / we are no longer individual; the individual is forgotten; we are only pure subject of knowledge; we are only that one eye of the world which looks out from all knowing creatures, but which can become perfectly free from the service of will in man alone. Thus all difference of individuality so entirely disappears, that it is all the same whether the perceiving eye belongs to a mighty king or to a wretched beggar; for neither joy nor complaining can pass that boundary with us. So near us always lies a sphere in which we escape from all our misery; but who has the strength to continue long in it? As soon as any single relation to our will, to our person, even of these objects of our pure contemplation, comes again into consciousness, the magic is at an end we fall back into the knowledge which is governed by the principle of sufficient reason; we know no longer the idea, but the particular thing, the link of a chain to which we also belong, and we are again abandoned to all our woe.”

Related Links:

Ad Reinhardt [IMAGELESS ICONS]

Ad Reinhardt | Prophetic Voices: Ideas and Words on Revolution